THE MITTEN’S MOST WANTED:

True Crime Featurettes

*This page is updated regularly.

THE MAYOR’S DAUGHTER

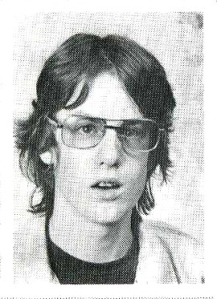

Usually when the child of a politician is kidnapped, it’s the plot of a bad action movie. But when the teenage daughter of newly retired Lansing Mayor Max Murninghan disappeared on July 9, 1970, it was simply a case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

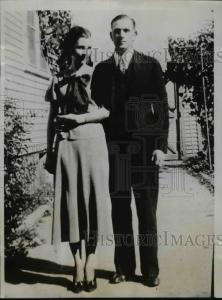

The Murninghans had just returned from a 4th of July vacation to New Hampshire, and this photo of a sunkissed Laurie was taken before she left for work on that fateful day.

Laurie had a part-time job at Gallagher’s Gifts and Antiques near the corner of Saginaw and MLK, where the patio area of El Azteco Restaurant now sits.

Mid-afternoon, a man entered the store and attempted to rob it. He got into a struggle with the owner, Mrs. Gallagher, and struck the elderly woman in the head with his gun. The gun went off and Mrs. Gallagher hit the floor, unconscious. Fearing he’d killed her, he couldn’t leave the only witness, 16-year-old Laurie, behind. He took the $64 cash that was in the register and absconded with Laurie in broad daylight, in one of the busiest areas in town.

But the man had no idea who Laurie was, or the lengths the city would go to to find her. Her father took up constant vigil at the Lansing Police Department. The FBI launched the largest manhunt in their history. Multiple agencies searched relentlessly for the missing girl.

All that manpower was for naught, however, as it was two young boys who discovered Laurie’s body in a swamp while they were out collecting soda cans on a rural country road.

The murder of the mayor’s daughter is one of the oldest cold cases in Lansing, although Laurie’s family maintains that the killer’s identity has been known all along. They claim that a career criminal and police informant, out of jail only because of his connections, committed the crime. That man died several years ago in California, without being held responsible for the death of Laurie Murninghan.

MICHIGAN’S TED BUNDY

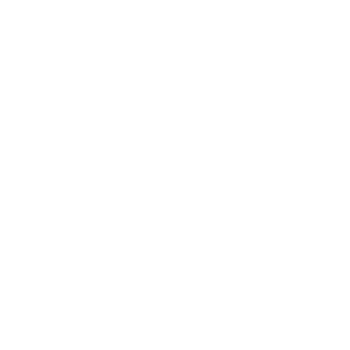

Donald Eugene Miller was the quintessential boy next door. Born and raised in East Lansing, Michigan, he was clean-cut and polite. A devoutly religious youth pastor and criminal justice major at Michigan State University, Don played the trombone in his college marching band and was known for his odd taste in attire. He also had a deadly fear of rejection, was obsessed with theghost of his dead fiancée, and would eventually be dubbed “Michigan’s Own Ted Bundy” by the media.

Miller’s first victim was his ex-fiancee, Martha Sue Young. She disappeared on New Year’s Eve 1976, just two days after she’d called off their engagement. After begging Martha Sue to go out with him that night, Donald Miller strangled her to death in his 1973 Olds Cutlass when she told him she didn’t love him anymore. He claimed to have dropped her off at home safely after their date, but was the prime suspect in her disappearance from the beginning. In the two and a half years between the night Martha Sue went missing and the day Miller led police to her remains in a Clinton County field, he would kill three more times.

A year and a half after Martha Sue disappeared, Miller set his sites on Marita Choquette, a Grand Ledge woman who reminded him of his former fiancée. The two women were the same height, same weight, and had the same wavy, shoulder-length brown hair and dark-framed glasses. Both women were very religious, and attended MSU. And both women met the same fate when they rejected Donald Miller. He strangled Marita Choquette in his car after taking her to breakfast one morning, then dumped her body in a field out in Holt, where it was discovered by a farmer two weeks after she went missing.

The same day Marita Choquette’s body was found, Wendy Bush disappeared from her Case Hall dorm. She too was a religious MSU co-ed who’d gone on a date with Donald Miller. He strangled her in the Spartan Stadium parking lot after she turned down his advances. He dumped her body in a ditch in Delta Township near where Our Savior Lutheran Church now stands.

Two months later, the wolf in sheep’s clothing was on his way home from work when he spotted a ghost. The petite woman with wavy, shoulder-length brown hair and big, dark rimmed glasses walking down the sidewalk near his home had to be Martha Sue Young. He ran her down with his car, then threw her into the backseat and began to strangle her, demanding to know how she was still alive. Only once he’d killed the woman did he realize that it wasn’t Martha Sue. It was his neighbor, Kristine Stuart, a Lansing school teacher.

Just two days after Kristine Stuart went missing, Donald Miller preyed upon his final victims. On August 16, 1978, he attacked a teenage girl in her Delta Township home after gaining entry by knocking on the door and asking to borrow a pencil and paper. Unaware that the girl was not alone, he was caught off-guard when her younger brother interrupted the attack. As he turned his rage on the boy, the girl escaped the house and was able to flag down help. Several people saw Miller flee from the home, and he was arrested later that day. Both teens survived.

Miller struck a plea deal with prosecutors that stunned the community. In exchange for a shockingly light sentence, he revealed the locations of his victims’ bodies. Martha Sue Young, Wendy Bush, and Kristine Stuart were all still classified as missing at the time, and their families desperately wanted closure. As a result, serial killer Donald Eugene Miller had his first parole hearing just TEN YEARS after his sentencing. He has been up for parole several times since then, each time being denied. His petition for parole will likely be reviewed again in 2021, when he is 66 years old.

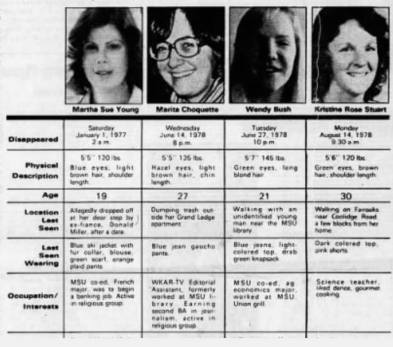

THE STRYCHNINE SAINT OF MICHIGAN

It’s been said that poison is a woman’s weapon. And while statistics prove that femme fatales typically use the same instruments as their male counterparts to exact their crimes (guns and knives being at the top of that list), there have been a number of female serial killers over the years that have used poison to kill. In England in the late 1800s, Mary Ann Cotton is believed to have killed upwards of 20 people with arsenic, including 11 of her own children. In the south, Nannie Doss killed close to a dozen people from the 1920s through the 1950s using rat poison. And in Michigan, there was Mary McKnight, who used strychnine as her weapon of choice to kill her entire family.

It’s been said that poison is a woman’s weapon. And while statistics prove that femme fatales typically use the same instruments as their male counterparts to exact their crimes (guns and knives being at the top of that list), there have been a number of female serial killers over the years that have used poison to kill. In England in the late 1800s, Mary Ann Cotton is believed to have killed upwards of 20 people with arsenic, including 11 of her own children. In the south, Nannie Doss killed close to a dozen people from the 1920s through the 1950s using rat poison. And in Michigan, there was Mary McKnight, who used strychnine as her weapon of choice to kill her entire family.

Born Mary Murphy, the future serial killer was born and raised in Kalkaska, Michigan. From 1887-1903, dozens of people died in her care, including: at least five of her own children, two husbands, the wife of her first husband’s business partner (and the first wife of her second husband), several infants and toddlers that were either related to her or the children of friends, her teenage niece, her sister, and finally her brother John Murphy, his wife Gertrude, and their baby.

All of Mary’s victims were poisoned with strychnine capsules that she often disguised as medicine. Many of them were ill and under her care at the time of their death. And all of them exhibited the same symptoms: twitching convulsions, foaming at the mouth, and excruciating pain. Until the deaths of the Murphy family, it was simply considered bad luck that so many people around Mary fell ill and died. Once investigators began to suspect foul play, Mary confessed pretty easily. She was sentenced to life in prison, but was released on parole after just 18 years. If estimates are accurate, that’s just one year in prison for each of her victims.

Suggested motives for the McKnight murders include money, jealousy, and mental illness. But one acquaintance claimed it was much simpler than that, saying: “She killed because she liked to go to funerals.”

THE WINDSOR WIFE SLAYER

The Wacousta Cemetery just northwest of Lansing dates back to the Civil War. Nestled among the thousands of aging headstones are those of the Lonsberry family- father William and mother Sarah, buried side by side, surrounded by several of their children. On a hilltop above the Looking Glass River, it’s a peaceful resting spot for a pioneer family. But if those graves could talk, they would tell a ghastly tale.

The Wacousta Cemetery just northwest of Lansing dates back to the Civil War. Nestled among the thousands of aging headstones are those of the Lonsberry family- father William and mother Sarah, buried side by side, surrounded by several of their children. On a hilltop above the Looking Glass River, it’s a peaceful resting spot for a pioneer family. But if those graves could talk, they would tell a ghastly tale.

On a hot July day in 1911, an Eaton County Deputy found himself in the company of a frail 85 year old woman by the name of Mary Lonsberry. She was in poor health, terrified, and desperate to tell a story about her son William that the entire community would soon know by heart.

William “Edgar” Lonsberry was born in Victory, New York in 1849. He married Sarah Wing when he was just 19, and the two moved to Michigan shortly after. They raised a family in Wacousta for many years before purchasing an 80 acre farm near Dimondale with the help of Sarah’s father. Their first home on the farm was a small stone shack, but they later built a much larger house. The couple had nine children together, six of whom lived to adulthood. After the children grew up and moved away, The Lonsberrys brought William’s elderly mother to live with them, and the three kept to themselves in the community.

William and Sarah had a tumultuous and sometimes violent relationship, often resulting in Sarah leaving home for weeks at a time. So no one thought much of it when she disappeared on New Year’s Day 1905. But when she didn’t return after a few weeks, eyebrows were raised. William told everyone she’d left him and run away to Canada. While most of the family, including son Herman who lived on the property adjacent to his parents, believed William’s story, not everyone was convinced. Sarah’s eldest son from a previous marriage and her and William’s youngest son Floyd were both convinced that William had murdered their mother. This accusation tore the family apart, and Sarah’s disappearance remained unsolved. The truth about what happened to her was hiding in plain sight, in the shack behind the house that was once the family home. But it would not come to be known until six years later.

According to William’s mother, Mary Lonsberry, the three were in the shack on New Year’s Day when William and Sarah began to quarrel over the deed to their farm. As Sarah’s father had financed the property, he was insistent that the deed be in her name to protect his investment. William felt that, as the man of the house, the deed should be in his name. Ownership of the land was a common source of contention for the aging couple, but on this day, William gave his wife an ultimatum- sign the deed over, or he would kill her. When she refused, he flew into a rage and choked her “until her eyes bulged out.” He then tossed her limp body to the ground, causing her to hit her head on a ceramic crock. She bled to death on the floor of the shack as her frightened mother-in-law looked on.

Afraid that his mother would turn him in, William locked her in the shack and kept her prisoner there for the next six years. He nailed one of the doors shut and barred the other from the outside. She spent day after day locked inside the blood-stained shack, tormented by the death of her beloved daughter-in-law, and tortured by her evil son, who abused and threatened her daily. Once, she escaped the shack and was making her way to a neighboring farm when William caught her and attempted to rip her tongue from her mouth with his bare hands. When neighbors heard her screaming, William explained that he was simply trying to get her back into the house and she was throwing a fit. When neighbors asked why she wasn’t allowed to leave, he said it was because she “told such awful stories.”

For over six years, Mary Lonsberry endured brutal treatment at the hands of her son before finding refuge with a shocked sheriff’s deputy, to whom she told her awful story. He took her into his home to keep her safe, and William was promptly arrested. William denied killing his wife, and maintained that she’d left him and moved to Canada. The children that stood by him all those years continued to believe him. Even though the floor of the shack behind the family home was stained with their mother’s blood. Even though their grandmother bore the physical scars of her son’s abuse. Even though the only other two possible witnesses to the crime, Lonsberry’s next door neighbors, died in a suspicious accident when their boat capsized in the Grand River near the Lonsberry property.

And then police found the body. Buried just two feet beneath the earth in the family’s sheep shed, Sarah Lonsberry’s decomposing corpse was found encased in lime. William had been walking across his wife’s crude burial site multiple times a day for years to tend to his animals, as had the couple’s son Herman, who often helped on the farm. The remains of Sarah Lonsberry were buried at Wacousta Cemetery beside three of her children that had died in their youth. William Lonsberry was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. The case was sensationalized in the media, and William became known as “The Dimondale Murderer” and “The Windsor Wife Killer.”

Still, his sons stood by him. They maintained that their grandmother was insane, and that their mother had been a “she-tiger” who often flew at their father in violent rages. He’d only killed her in self-defense. After the trial, Mary Lonsberry was sent to live with the grandsons who spoke so ill of her. She died less than a year later under suspicious circumstances. When police arrived to investigate, they found that her body had already been embalmed and prepared for burial, erasing any evidence of foul play.

When William Lonsberry died 20 years after murdering his wife, he was buried beside her in the family plot at Wacousta Cemetery. Father and Mother. Together forever.

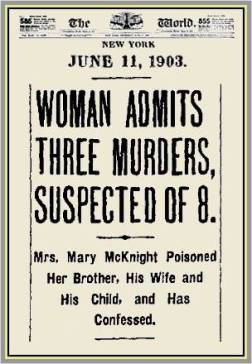

THE WOLF OF NORTH FOX ISLAND

When he first purchased North Fox Island, an 840 acre patch of dense forest in the northern waters of Lake Michigan, millionaire philanthropist Francis Shelden took seven whitetail deer with him, purchased from a farm in Charlotte, MI. He hoped to establish a whitetail population on his private island. When the deer began to overrun the land, he spoke of bringing wolves in to balance things out. But there was already a wolf on North Fox Island. And it wasn’t interested in deer as prey.

When he first purchased North Fox Island, an 840 acre patch of dense forest in the northern waters of Lake Michigan, millionaire philanthropist Francis Shelden took seven whitetail deer with him, purchased from a farm in Charlotte, MI. He hoped to establish a whitetail population on his private island. When the deer began to overrun the land, he spoke of bringing wolves in to balance things out. But there was already a wolf on North Fox Island. And it wasn’t interested in deer as prey.

An heir to the Detroit Edison fortune, Ann Arbor native Francis Shelden was an investor, a pilot, a Yale graduate, and a geologist- among other things. He was on the board of directors at Cranbrook Boarding School, and volunteered regularly at Big Brothers of America. And then in 1960, when he was just 32 years old, he bought his own island. Located in the depths of Lake Michigan between the upper and lower peninsulas about 30 miles northwest of Charlevoix, Shelden claimed he intended to turn the island into a resort. He razed the forest to put in an airstrip, and built a sleek glass and timber home atop a dune. He paved roadways and sectioned off the land into individual parcels. But the resort never opened. And Shelden’s true intentions for North Fox Island would not be revealed until years later.

In December 1975, Francis Shelden and North Fox Island were featured in a lengthy article in the Detroit Free Press. He shared that he had changed his mind about the resort and intended to keep the island private, as a nature preserve and hunting camp for himself and a few close friends. What the in-depth article failed to reveal was that in June of 1975, Shelden incorporated an organization called Brother Paul’s Children’s Mission. Touted as a nature and rehabilitation program for troubled youth, the organization was geared toward boys from ages 12-15, mostly from poor neighborhoods near Detroit. Shelden used government subsidies and donations from the public to fly juvenile delinquent teenage boys from southern Michigan to his private island up north for a week of rest, relaxation, and rehabilitation.

In reality, North Fox Island was being used as a base for an international child pornography ring. For over a year, Francis Shelden preyed on young boys from poor communities, taking them to his secluded island where his millionaire friends would fly in to help him manufacture, observe, and take part in the production of child pornography. The truth about Brother Paul’s Children’s Mission began to unravel when a school teacher in Port Huron was arrested for crimes against children in July 1976. He was found in possession of material produced on North Fox Island, and pointed the finger at Francis Shelden as the ringleader.

Shelden fled the country before he could be apprehended, as did the rest of his millionaire friends implicated in the scandal. An entire network of wealthy, influential men avoided prosecution for their crimes against hundreds of Michigan teenagers, perpetrated under the guise of community service. Only one of the men, the school teacher from Port Huron, was ever sent to prison. He served two years.

North Fox Island is now owned by the state, and is advertised as a nature preserve. The infamous airstrip through the center of the island is still intact. Francis Shelden is believed to have died in the Netherlands after many years in hiding. Most of his accomplices were never caught, although one, a young man by the name of Christopher Busch, became known for another reason entirely. But that’s a story for another time…

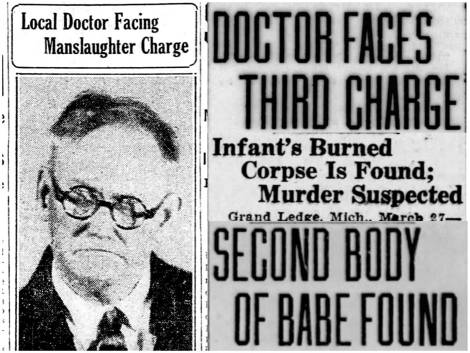

THE BABY SLAYER OF GRAND LEDGE

Downtown Grand Ledge is about as picturesque as a small town can get. The flag-lined bridge that stretches over the Grand River, the small businesses in charming vintage buildings, the century old homes, the little league baseball field under the bridge. It’s a city that celebrates tradition and rich history. But it hides a dark past, including the shocking case of the demented Dr. Howell.

Downtown Grand Ledge is about as picturesque as a small town can get. The flag-lined bridge that stretches over the Grand River, the small businesses in charming vintage buildings, the century old homes, the little league baseball field under the bridge. It’s a city that celebrates tradition and rich history. But it hides a dark past, including the shocking case of the demented Dr. Howell.

On March 25, 1925, a sheriff’s deputy was called to the Odd Fellows Hall on Bridge Street. There was a pack of aggressive dogs out behind the building, and neighbors were frightened. But it wasn’t the dogs they needed to fear. The young officer was horrified to find that the source of the dogs’ frenzy was the partially cremated body of a newborn baby. In shock, he rushed the baby to the town coroner and called for backup. The coroner determined that the baby was roughly a week old at the time of its death, and had been dead about 48 hours. The townsfolk couldn’t believe it when the news broke- someone had murdered an infant, burned its body, and dumped it behind a building in the busy downtown area. It was a shocking crime for such a small, quiet community. But the terror was just beginning.

Five days later, on March 30th, two young boys playing at the Grand Ledge city dump found the body of a second infant, dead less than 24 hours, wrapped in the Sunday comics from the local newspaper. What was at first being investigated as an isolated incident quickly became something else entirely. There was a baby slayer in Grand Ledge. Police suspected that someone in the area was offering a for-hire service to “take care of” unwanted babies, and feared that more young bodies would be found. They zeroed in on a suspect almost immediately.

Dr. Maurice Howell of Lansing was no stranger to authorities. Six months before the dead babies turned up in Grand Ledge, Dr. Howell was charged with manslaughter for the death of 17 year old Ida Druce, who died at Sparrow Hospital in Lansing following complications from an illegal abortion. On her deathbed, she named Dr. Howell as the man who’d performed the surgery. Just weeks later, Dr. Howell was arrested in his Downtown Lansing office for furnishing illegal liquor (1920s = prohibition). He was found in possession of moonshine, whiskey, and cocaine. During this time, he was also under federal investigation for illegally selling narcotics.

Less than a month after the murdered babies were found, and with both cases still unsolved, three teenage girls were admitted to Sparrow Hospital during a one week time frame, all suffering from complications of illegal abortions. Dr. Howell had performed all of the surgeries. He was arrested, and was therefore already behind bars when the mother of one of the dead babies came forward. 16-year old Flossie Corlow and her mother admitted to authorities that they paid Dr. Howell a sum of $25 to perform an abortion for Flossie, who was newly married. But the young girl was further along than originally thought, and when the baby was delivered, it was alive. Dr. Howell offered to “take care of things.” (For an additional charge, of course.)

Banned from practicing medicine at Sparrow Hospital and expelled from the Ingham County Medical Society, it is believed that Dr. Howell began performing back alley abortions and disposing of unwanted infants for quick cash to fuel his drug addiction. He preyed upon desperate young girls and their helpless babies, and is believed to be responsible for dozens of unreported deaths.

Dr. Howell was charged with manslaughter for the deaths of Ida Druce and Flossie Corlow’s baby. He was charged with multiple counts of “performing an illegal operation” for his life-threatening abortions. And he was indicted in federal court on narcotics charges. He was also suspected in the death of the unidentified baby whose burned body was found behind the Odd Fellows Hall, and of performing countless other illegal abortions and infanticides. In October 1925, he was convicted and sentenced to six months to one year in prison. SIX MONTHS TO ONE YEAR. He died in May 1932 after a lengthy, excruciating illness, during which both of his legs were amputated. (Yay, karma!) His gruesome legacy died with him. But the trauma he inflicted on the Grand Ledge community lasted a lifetime for his victims.

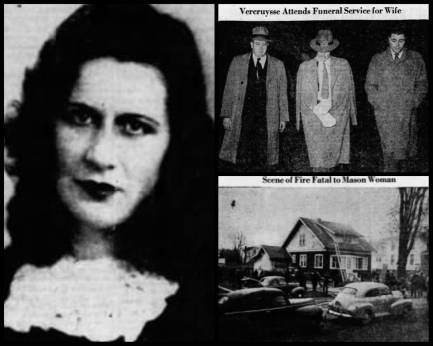

THE MASON TORCH MURDER

On January 14, 1949, the peaceful quiet of a winter afternoon was shattered by the tortured screams of a woman coming from her Center Street home in downtown Mason. Moments later, her frantic husband delivered her to the town hospital, where she worked as a nurse. She was burned from head to toe, her clothes melted off, her face grossly disfigured. Her husband was burned as well, on his arms and hands. Once medical personnel separated the two for treatment, they would tell very different stories about what happened.

On January 14, 1949, the peaceful quiet of a winter afternoon was shattered by the tortured screams of a woman coming from her Center Street home in downtown Mason. Moments later, her frantic husband delivered her to the town hospital, where she worked as a nurse. She was burned from head to toe, her clothes melted off, her face grossly disfigured. Her husband was burned as well, on his arms and hands. Once medical personnel separated the two for treatment, they would tell very different stories about what happened.

43 year old Belgian immigrant Victor Vercruysse, a local carpenter and stonemason, told officials that he and his wife were working in the basement when a can of paint remover exploded and caused a flash fire. He claimed his hands were burned when he attempted to save his wife. By all accounts, he was distraught, and seemed concerned only with comforting her. When she asked about her face, he told her: “Never mind your face, you’ll always be beautiful to me,” to which she responded, “Oh, Vic, why did you do it?”

According to 41 year old Selina Vercruysse, her husband called her down into the basement after an uneventful trip to the grocery store, during which neighbors reported that both Mr. and Mrs. Vercruysse were joking and in good spirits. Selina assumed Vic needed her help with something, but when she reached the bottom of the stairs, he threw gasoline in her face and lit her on fire, turning her into a human torch. When she tried to escape the basement, he blocked her exit. She eventually made it up the stairs and out to the back yard, where she began screaming for her life. Her husband chased after her, carried her back into the house, and took her back down to the basement, which was engulfed in flames. That was how he burned his hands- putting her back into the fire, not pulling her out of it. He refused to take her to the hospital until she promised not to tell anyone what happened. But as a nurse, Selina understood the severity of her injuries, and knew she didn’t have much time. She told anyone who would listen what happened to her, so that there would be as many witnesses as possible. She was concerned for her children, and wanted to make sure they were protected.

When asked why her husband set her on fire, she said: “He was always so jealous. He said if he couldn’t have me, nobody else would. I don’t know why he did it. I’ve always been true to him.” Selina Vercruysse succumbed to her injuries within hours of her arrival at the hospital. She was a mother of five- three adult daughters, and a young daughter and son still at home. Her husband was charged with first degree murder, and the case was dubbed “The Torch Murder” by the media.

While in custody, Vic Vercruysse repeatedly attempted suicide and tried to escape. They chained him to his bed. That didn’t work. They put him in a straitjacket. That didn’t work. He was so mad with grief, he was declared incompetent to stand trial, and was committed to the Ionia Asylum for Insane Criminals. He was released quietly some time later, and lived as a free man until he passed away in 1983. In death, his wish finally came true- no one else would ever have his wife. He was buried beside her in a Michigan cemetery.

THE MARBLE MURDERS

Near the corner of Hagadorn and Burcham in East Lansing sits a quaint 150-year-old home with a deadly history. In the late 1800s, it was the scene of a fatal shootout that shocked the normally quiet neighborhood.

John Marble was East Lansing’s first entrepreneur and a leader in the community. He purchased his family home in 1860, and operated a successful farm and sawmill. A few years later, he purchased an old tollhouse and moved it onto his property for his live-in farmhand, William Martin, and Martin’s family. It would prove to be a lethal mistake.

In 1865, tragedy struck the Marble home for the first time. John’s wife died, leaving him to care for four children on his own. He hired a live-in housekeeper to assist him, a considerably younger woman named Emily Chapman who had a son of her own. John and Emily married about a year later. But their union was not a happy one, and the age difference between them was believed to be a contributing factor. After about a decade of miserable matrimony, John moved out of the home and rented the property to Emily while he stayed with friends. It was then that the rumors began.

John and Emily’s marriage was not the only unhappy one on the Marble estate. Farmhand William Martin’s family was falling apart as well. At one point, he was arrested for non-support of his wife and children. And guess who bailed him out of jail? His boss’s wife, Emily Marble.

Emily, William, and Emily’s son Willard Chapman, who was now an adult, lived on the Marble property together in spite of the accusations being made by townsfolk. Emily and William were arrested for adultery at one point, but later released. John Marble was humiliated and disgraced. He planned to divorce his wife on the grounds of adultery, but Emily and William had another plan. Friends told John that Emily and William were planning to strip his home of its property, sell the stolen goods, and use the money to flee the country together.

On the night of November 12, 1876, John Marble and two friends, John Morley and Charles Ayers, rode out to the Marble estate to assess the situation. They tethered their horses in the woods and sneaked onto the property. While they were watching through the windows of the house, hoping to witness some sort of illegal activity, Emily became aware of the intruders. Her son grabbed a shotgun, while she and William armed themselves with revolvers. They headed outside looking for a fight.

When they happened upon John Marble and his friends, a shoot-out commenced. Emily’s son shot one of his stepfather’s friends in the head at point-blank range, killing him instantly. He then ran down John’s other friend, who was fleeing into the woods, and bludgeoned him with the butt of the shotgun, crushing his skull. In response, John began shooting at his stepson, hitting him once in the arm and once in the neck. His stepson fired back, hitting John in the shoulder. Emily and William were not injured.

John Marble was seriously injured in the shoot-out at his estate. His friends Charles Ayers and John Morley were killed. His stepson Willard Chapman was also seriously injured, but recovered. Chapman, along with his mother Emily Marble and her lover William Martin, was convicted of second degree murder and sentenced to state prison. John Marble sold the property where the shoot-out occurred six months later.

If you are familiar with the area, and find yourself wondering if Marble Elementary School and the Marble subdivision might be named after the Marble family, the answer is yes. Yes, they are.

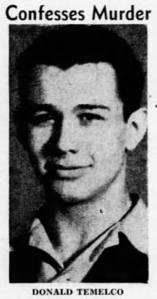

THE IONIA LADY KILLER

At 17, Donald Temelco was living the American dream. His parents owned a successful restaurant in the small town of Ionia, Michigan. He was a high school football star. He was popular. Charismatic. Handsome. A real lady killer.

At 17, Donald Temelco was living the American dream. His parents owned a successful restaurant in the small town of Ionia, Michigan. He was a high school football star. He was popular. Charismatic. Handsome. A real lady killer.

On February 27, 1943, Don joined some friends at the local juke joint in town, a spot with a reputation for playing fast and loose with the legal drinking age. He was hoping to meet up with a girl he’d been seeing. But his night didn’t go as planned, and he was humiliated in front of his peers when the girl left with another boy shortly after midnight. Furious, Don started drinking and set his sights on another girl, a casual acquaintance named Clara Johnson. Clara was 18- pretty, blonde, and a war worker at the local factory in the final years of World War II. Clara had just finished her shift, and stopped by the tavern on her way home. She and Don flirted, had a few drinks, and then left the bar together around 1am.

The following morning, Clara’s partially frozen, mutilated body was found near the tavern in a back alley coal bin by a freight worker. She’d been bludgeoned with a 2×4 and an iron fence post, then strangled with her own undergarments, which were still knotted around her neck. She was so badly beaten, she was nearly unrecognizable. Donald Temelco, the prime suspect in her murder, was nowhere to be found.

The 6’1, 214 pound teenager was apprehended three days later in Canada, over 700 miles from home. He turned up at a Montreal diner in bloody clothes with scratches on his hands and face. Broke and afraid, he called his mother and asked her to wire him $50. She called the police instead. He was picked up while he waited at a train station for his money to arrive, and was extradited back to Michigan after confessiong to Clara’s murder. When asked why he killed her, Don said: “I was in an ugly and mean mood all night. A funny feeling came over me. I suddenly turned on her and strangled her and kicked her head and face. I don’t know why I did it.”

Donald Temelco was charged with first degree murder at the age of 17. So many people turned out for his trial that the proceedings had to be moved to a bigger building, and the judge barred anyone under the age of 21 from attending. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. 20 years later, Governor George Romney commuted his sentence, and he was paroled at the age of 37.

Don moved to Pennsylvania, married, and had one child. The baby died in its first month of life. Don lived to a ripe old age. After his death, he was reincarnated as the youngest (and most talented) Jonas brother, Nick.

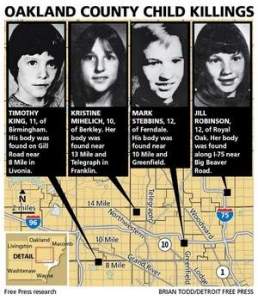

THE OAKLAND COUNTY CHILD KILLER

Time has a way of burying unpleasant things. Sometimes a bigger, better story comes along and the media moves on. Sometimes the police investigation runs cold. Sometimes the shouting turns to whispers and then to silence. Even the most shocking, sensational stories fall victim to time. Maybe that’s why the Oakland County Child Killer is little more than a distant memory in Michigan, where he preyed on the most innocent members of society in the 1970s. Much remains unknown about the OCCK, including his identity and his true number of victims. He is believed to be responsible for the deaths of at least four children- two boys and two girls, all white, all from middle class families in the Detroit area.

Time has a way of burying unpleasant things. Sometimes a bigger, better story comes along and the media moves on. Sometimes the police investigation runs cold. Sometimes the shouting turns to whispers and then to silence. Even the most shocking, sensational stories fall victim to time. Maybe that’s why the Oakland County Child Killer is little more than a distant memory in Michigan, where he preyed on the most innocent members of society in the 1970s. Much remains unknown about the OCCK, including his identity and his true number of victims. He is believed to be responsible for the deaths of at least four children- two boys and two girls, all white, all from middle class families in the Detroit area.

The OCCK’s first victim was 12 year old Mark Stebbins of Ferndale, a suburb of Detroit. Mark disappeared on the afternoon of February 15, 1976 while walking home from the local American Legion Hall, where his mother was working. He told her he was going home to watch television, and then was never seen again. His body was found four days later in Southfield, a small town about five miles from Ferndale. He’d been beaten and strangled. There were rope marks on his wrists and ankles, which indicated he’d been bound during his captivity. Police believed he’d been kept alive for at least a couple of days before being killed. While the crime was horrific, the most unsettling thing about it was the condition of the body. Mark was found laid out neatly on a snowbank in the parking lot of an office building. His clothes, the same ones he was wearing the day he disappeared, had been recently cleaned and pressed. His body appeared to have been bathed, and his nailbeds had been cleaned. The case made national headlines, but remained unsolved.

Ten months later, on December 22, 1976, 12 year old Jill Robinson packed a bag following an argument with her mother and ran away from her home in Royal Oak, a town about two miles from Ferndale. The following day, her bicycle was found abandoned behind a store in her neighborhood. Four days after her disappearance, her body was found neatly laid out on a snowbank within view of the Troy Police Department, less than 20 miles from her home. She was fully clothed, still wearing her backpack, and had been shot in the face with a shotgun. She showed the same signs of recent grooming as Mark Stebbins. The similarities between the murders could not be ignored, but police were hesitant to attribute them to the same killer at first. Any doubt as to whether the crimes were connected was put to rest, however, when another child disappeared a week later.

On January 2, 1977, 10 year old Kristine Mihelich went to purchase a magazine from the 7-Eleven near her house in Berkley, just a few miles from where Jill Robinson had disappeared a week earlier. She never returned home. Nineteen days later, her body was discovered by a mail carrier in Franklin Village, less than ten miles from her hometown. She, too, was found neatly laid out on a snowbank, fully clothed. She’d been recently bathed, and her nailbeds were freshly cleaned. Investigators determined she’d been smothered to death, and that she’d been dead less than 24 hours, which meant she’d been held captive for nearly three weeks before she was killed.

There was officially a serial killer on the loose in Oakland County. The media dubbed him “The Babysitter” due to the way he meticulously groomed the children before murdering them. Mass hysteria ensued. Authorities launched the largest manhunt in the country, and parents were hyper-vigilant. Still, one more child would fall victim to the Oakland County Child Killer.

On March 16, 1977, two months after and five miles down the road from where Kristine Michelich’s body was found, 11 year old Timothy King borrowed 30 cents from his sister to buy candy from the drugstore down the street from their home in Birmingham. He left with his skateboard tucked under his arm, and was never seen alive again. During the six days he was missing, authorities searched tirelessly. The OCCK’s previous victim was held captive for weeks before she was killed, so there was hope for Timothy. On that hope, his parents made emotional pleas to local news outlets. His mother was quoted as saying that she hoped he could come home soon so that she could serve him his favorite meal, Kentucky Fried Chicken. But on March 22, 1977, Timothy’s body was found in a shallow ditch in the city of Livonia, about a half hour from his home. He’d been laid out neatly along the side of the road, his skateboard beside his body. His clothing had been pressed and washed. There were rope marks on his wrists and ankles, and he’d been suffocated to death less than six hours before he was found. But the desperate pleas of his family hadn’t entirely fallen on deaf ears. During his autopsy, investigators found that he’d eaten fried chicken shortly before he was killed.

The Oakland County Child Killer was never caught, and remains anonymous to this day. Many suspects were investigated over the years, including a wealthy young man by the name of Christopher Busch. Busch, the son of a high-level GM executive, grew up in the Detroit area’s wealthiest suburbs and attended boarding school in Switzerland. His parents, who had him late in life, were said to travel abroad regularly, and often left their entitled son to his own devices. Christopher Busch was a troubled young man. Since his teens, there had been rumors of inappropriate conduct with younger boys. Every time an accusation was made, it mysteriously went away without incident. It was believed that his parents paid off his victims to keep him out of trouble. He was arrested multiple times in the late 1970s, but his parents bailed him out promptly every time, and the charges always disappeared. He was implicated in the North Fox Island child pornography scandal of 1976, when he was caught with eight rolls of film that were confiscated as evidence in the case. He lived in Birmingham, the same town as Timothy King, at the time. The OCCK’s reign of terror began a few months after the North Fox Island pornography ring was shut down. Christopher Busch, at one point the prime suspect, was subjected to a lie detector test in the OCCK case. He failed. In November 1978, he committed suicide in his parents’ mansion at the age of 27, never having admitted to or been charged with the child killings in Oakland County. But when the troubled life of Charles Busch ended, so did the murders. And the case that had once terrorized the suburbs of Detroit, and the nation, slowly faded into obscurity.

THE COLDWATER GIRL

On January 30, 1891, two men crossing the frozen Grand River near Dimondale spotted something out of place. Tangled in nearby branches was the nude body of 11-year-old Nellie Griffin, a local orphan. When the men pulled her out of the water, her body was still warm. The tale of the murdered child was so tragic that a horde of nearly 500 men gathered, intent on lynching her killer. But the truth about Nellie Griffin’s life was even sadder than her death. The doe-eyed brunette had been thrown away long before her body was tossed into a hole in the ice. And the community that was so outraged over her death was partly to blame.

On January 30, 1891, two men crossing the frozen Grand River near Dimondale spotted something out of place. Tangled in nearby branches was the nude body of 11-year-old Nellie Griffin, a local orphan. When the men pulled her out of the water, her body was still warm. The tale of the murdered child was so tragic that a horde of nearly 500 men gathered, intent on lynching her killer. But the truth about Nellie Griffin’s life was even sadder than her death. The doe-eyed brunette had been thrown away long before her body was tossed into a hole in the ice. And the community that was so outraged over her death was partly to blame.

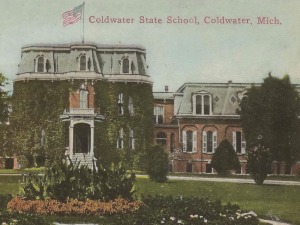

On January 27, 1891, a man calling himself E. Hendershot contacted the state orphan asylum in Coldwater and expressed his desire to adopt a young girl. He claimed to be a farmer in Parma with a wife and two children at home. Arrangements were made, and the next day the graying man in his 50s arrived at the orphanage alone. He was shown around the facility, and was allowed to hand-pick his new “daughter.” A beautiful girl with dark hair and dark eyes, he zeroed in on Nellie Griffin quickly. But the young girl, who was said to be wise beyond her years, was no ordinary orphan.

Born in Mason, MI in September 1879, Nellie Griffin was the daughter of a wealthy (but feeble minded) young man and a former servant girl with an untoward reputation. The union between the young couple was tumultuous, and they split when Nellie was three. Her mother abandoned her, leaving her with her in the care of her parents. Nellie’s maternal grandparents quickly turned the toddler over to her father and his family. While Nellie’s father was inept, his parents were very well known in town. Nellie’s grandfather, R.F. Griffin, was the first mayor of Mason, and remained active politically after his term ended. He controlled property all over town, but the one thing he couldn’t control was his granddaughter. Shortly after Nellie’s parents separated, her father ran away to California. So in her first few years of life, Nellie had been abandoned by her mother, her maternal grandparents, and her father. The Griffins were all she had left. But they had a reputation to uphold, and Nellie’s “waywardness” became a source of embarrassment for them. So much so, that when she was just eight years old, the Griffins signed away custody and sent her to the state orphanage in Coldwater, where she would live for over two years before being adopted by the man who called himself Mr. Hendershot.

After hand-picking his new daughter, Mr. Hendershot was sent away from the orphanage for the night while the school’s superintendent investigated. He was suspicious of the odd man, so he called upon the county commissioner to conduct a “background check” and call him if he found any reason why Mr. Hendershot should not be allowed to take the girl. The next morning, having heard nothing back from the commissioner, the superintendent signed off on the adoption, and sent Nellie off with her new father.

But there was a reason the commissioner never called the superintendent back. He was having a hard time finding any record of Farmer Hendershot. Why? Because he did not exist. The man who’d absconded with Nellie Griffin was a 54-year-old divorced farmhand from the Lansing area named Russell Canfield, who got it in his head that he wanted a young girl, so he went and got one. The two traveled to Eaton County by train, and then set off on foot through the woods toward the farm where Canfield worked. According to his testimony, the two sat on a felled log to rest, and Nellie began to cry because she was cold. For no reason that he could ever explain, Canfield became enraged and strangled Nellie to death. He then removed all of her clothing so that she would sink faster, carved a hole into the ice of the Grand River, and tossed her in. He was counting on the fast-moving currents to carry her body far away from the scene of the crime. He was not counting on her body becoming tangled in branches.

When news broke of Nellie Griffin’s murder, an angry mob swelled to nearly 500 men, prepared to storm the arresting officers on their way to the jail so that they could lynch Russell Canfield at once. Police told the mob that they were taking Canfield back to the scene of the crime to force a statement. But as the mob headed toward the Grand River, officials hurried Canfield out of town, to the Eaton County Jail in Charlotte. Five days later, Canfield was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. Even in death, poor Nellie’s family didn’t want her, and she was buried in the now defunct cemetery at the state orphanage in Coldwater.

So let’s summarize, shall we? At the age of THREE, a little girl was abandoned by her mother. Shortly after, she was turned away by her maternal grandparents, then abandoned by her father. At the age of EIGHT, her paternal grandparents sent her to an orphanage at the urging of their neighbors, who considered the child a nuisance. And at the age of ELEVEN, she was handed off to a strange old man using a fake name who picked her out of a lineup of available orphan girls. She was promptly murdered, and then thrown away one final time. Then and only then did the community that failed Nellie Griffin so many times care about what happened to her. How demented is that?

Did you know that Michigan was the first English-speaking government in the world to abolish the death penalty? The Mitten officially outlawed the practice in 1846, but had ceased sentencing prisoners to death long before that date. In fact, there had been no executions in Michigan since before it joined the Union in 1837. And then came along Anthony Chebatoris.

Did you know that Michigan was the first English-speaking government in the world to abolish the death penalty? The Mitten officially outlawed the practice in 1846, but had ceased sentencing prisoners to death long before that date. In fact, there had been no executions in Michigan since before it joined the Union in 1837. And then came along Anthony Chebatoris.

On September 29, 1937, career criminals Anthony Chebatoris and Jack Gracy bungled a robbery of the Chemical State Savings Bank in Midland, MI. What was supposed to be a simple cash grab quickly escalated out of control. Chebatoris shot bank president Clarence Macomber and cashier Paul Bywater before fleeing the building with his accomplice. Having heard the commotion, Dentist Frank Hardy, who had a practice next door to the bank, grabbed his rifle and began firing on Chebatoris and Gracy as they fled the scene, causing them to crash into a parked car.

Unable to determine who was shooting at them, Chebatoris began firing wildly into the street as he and Gracy attempted to make their getaway on foot, both wounded. Chebatoris had been shot in the arm, while Gracy had been injured in the crash. Chebatoris shot truck driver Henry Porter before stealing a vehicle driven by a young mother, who just barely got her baby out of the car before the criminals drove off. The vigilante dentist fired upon the bank robbers again, hitting the gas tank of their stolen vehicle. They abandoned the car and were attempting to steal a lumber truck when Dr. Hardy fired again, killing 28-year-old Jack Gracy instantly. Witnesses say the entire back of Gracy’s head was blown off. With his accomplice dead, Anthony Chebatoris was on his own. He took off running down the railroad tracks, unsuccessfully attempting to steal two more vehicles along the way. Exhausted and wounded, he was apprehended by a horde of construction workers and townsmen, who held him until police arrived.

As robbery of an FDIC insured bank is a federal offense, Chebatoris was charged in federal court with robbery, assault, and later murder after truck driver Henry Porter died from his injuries. Since the case was tried on the federal level instead of the state level, the U.S. District Attorney’s office was able to seek the death penalty. On October 28, 1937, Chebatoris was found guilty on all charges and sentenced to die. Despite attempts by Michigan’s governor to have his sentence commuted to life in prison, then to at least have the execution moved to another state, Anthony Chebatoris was sent to the gallows at the Federal Detention Farm in Milan, Michigan. He was hanged at dawn on July 8, 1938 in front of 23 witnesses, making him the only prisoner ever executed in the State of Michigan.

In the dark of night on November 22, 1883 , 16-year-old farmhand George Bolles awoke to roaring thunder at the Crouch farm in Jackson, MI. He looked outside and, through the blinding rain, thought he saw a man with a lantern standing on the property. He heard a thud. Then another, and another. Then a scream. Terrified, he climbed into a trunk on the second floor of his employer’s home and stayed there all night. The gruesome discovery he made the following morning is one locals still talk about to this day.

In the dark of night on November 22, 1883 , 16-year-old farmhand George Bolles awoke to roaring thunder at the Crouch farm in Jackson, MI. He looked outside and, through the blinding rain, thought he saw a man with a lantern standing on the property. He heard a thud. Then another, and another. Then a scream. Terrified, he climbed into a trunk on the second floor of his employer’s home and stayed there all night. The gruesome discovery he made the following morning is one locals still talk about to this day.

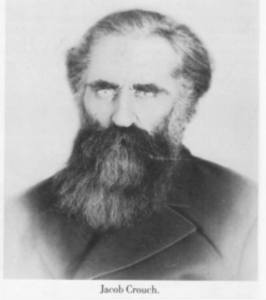

74-year-old farmer Jacob Crouch had been murdered, shot in the head. Also dead were his daughter Eunice, who was eight months pregnant, and her husband Henry White. Eunice had been shot four times, while Henry had been shot twice. Moses Polly, a cattle buyer from Pennsylvania who was staying with the Crouch family that night, was shot and killed as well. The only ones left alive in the home were Bolles, the teenage farmhand, and live-in servant Julia Reese. The pair were arrested on suspicion of murder solely because they survived the massacre, but were quickly released due to a lack of evidence. The sheriff called in a professional to photograph the whites of Eunice’s eyes, to see if the killer’s image was still reflected. Shockingly, that yielded no results. (But only because too much time had passed!) Some theorized that traveling gypsies or bandits passing through town were responsible, and that the family had been murdered during a robbery gone wrong. But others believed the answer was much more sinister.

Jacob Crouch and his wife Anna had five children- Susan, Eunice, Dayton, Byron, and Judd. Anna died in 1859, six days after giving birth to Judd. Judd was raised by his eldest sister Susan and her husband Daniel, who he thought were his parents until he was 10-years-old. Eunice was well-known to be Jacob’s favorite. It was rumored that he was leaving his entire fortune (said to be worth millions) to Eunice’s unborn child, and the others were less than thrilled to be cut out of the will.

Dayton Crouch died mysteriously just months before his father, sister, brother-in-law, and unborn niece or nephew were murdered. Susan Crouch-Holcomb died only a few months after bloodbath at the farm. Some said she’d been fed rat poison, while officials ruled it a suicide. With Byron and Judd the only remaining members of the Crouch family, they both came under suspicion for the murders. Susan’s husband Daniel Holcomb and her brother/son Judd were charged with the murders in 1884. Daniel was acquitted, and Judd was never brought to trial. Officially, the murders remain unsolved.

In the end, Judd Crouch got what so many believed he was after- the family farm. He later lost the property to the bank, and died in 1946. The house fell victim to arson the following year, and was destroyed in 1947.

MICHIGAN’S FIRST SCHOOL SHOOTER

On February 22, 1978, the students at Everett High School in Lansing were preparing to go home for the day when an unfamiliar sound echoed through the halls- once, twice, and then a third time. As a flurry of white feathers and frantic screams filled the air, one word was repeated, over and over: GUN. Pandemonium ensued. When it was over, 15-year-old Bill Draher was dead on the floor near his locker, lying in a puddle of blood mixed with feathers from his down-filled jacket. 16-year-old Kevin Jones was on his way to the hospital with a bullet wound to the head. And 15-year-old Roger Needham, described by some as a misunderstood loner who was a victim of intense bullying, and by others as a Nazi-enthusiast who tormented other students and talked about blowing up the school, sat in the principal’s office waiting for his father to pick him up after becoming the third school shooter in American history.

On February 22, 1978, the students at Everett High School in Lansing were preparing to go home for the day when an unfamiliar sound echoed through the halls- once, twice, and then a third time. As a flurry of white feathers and frantic screams filled the air, one word was repeated, over and over: GUN. Pandemonium ensued. When it was over, 15-year-old Bill Draher was dead on the floor near his locker, lying in a puddle of blood mixed with feathers from his down-filled jacket. 16-year-old Kevin Jones was on his way to the hospital with a bullet wound to the head. And 15-year-old Roger Needham, described by some as a misunderstood loner who was a victim of intense bullying, and by others as a Nazi-enthusiast who tormented other students and talked about blowing up the school, sat in the principal’s office waiting for his father to pick him up after becoming the third school shooter in American history.

Kevin Jones, who’d been shot in the head and watched his best friend die in front of him, attempted to return to school a week after the shooting. But when school officials suggested that his presence might be too upsetting for his classmates and that he might do better at an alternative ed facility, Jones left the building and never went back. Not to Everett, or to any other high school. He worked a string of blue collar jobs before complications from diabetes forced him to move back in with his mother, and he died at the age of 37.

Meanwhile, Roger Needham, the son of a prominent legal professor, was tried as a juvenile and pleaded no contest to first degree murder. He earned his high school diploma while incarcerated and began taking classes at the University of Michigan under close supervision. When he turned 19, he was released from custody and his records were sealed. He continued his education at U of M and eventually went on to earn his PhD. He became a college professor, and was once employed by the City College of New York. He is now a resident of Hastings On Hudson, an upscale community in upstate New York.

40 years later, there are so many stories about school shootings, it’s hard to keep them all straight. This story is one of the very first- about an angry young man who stole the life of one student and the future of another, but was handed opportunity and success nonetheless.

THE KILLER CON-MAN

In 1892, Lizzie Borden was arrested for the grisly murders of her father and step-mother in Fall River, Massachusetts. The case made headlines around the world, partly because of the salacious details of the crime, and partly because a child killing their parents was simply unthinkable. But it had happened before, just a few years earlier in Jackson, Michigan.

In 1892, Lizzie Borden was arrested for the grisly murders of her father and step-mother in Fall River, Massachusetts. The case made headlines around the world, partly because of the salacious details of the crime, and partly because a child killing their parents was simply unthinkable. But it had happened before, just a few years earlier in Jackson, Michigan.

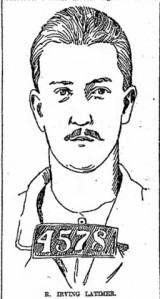

The Latimer family moved to Jackson in the 1880s, where patriarch Robert Latimer opened a drugstore. The business did exceptionally well, and the family became well-to-do. At the height of his success, 57-year-old Robert Latimer died suddenly of what was believed at the time to be a heart attack. He left behind his wife Sarah and one son, 22-year-old Robert Jr., who went by his middle name, Irving.

Robert had a sizeable life insurance policy, of which his wife Sarah was the sole beneficiary. Sarah was known to loan her son Irving large sums of money from her inheritance, which he promised to pay back but never did, resulting in her cutting him off financially.

On January 25, 1889, just a little over a year after Robert Latimer’s sudden death, maintenance workers arrived at the Latimer mansion to find Sarah Latimer murdered, shot dead with a pistol that belonged to her son. Irving Latimer was arrested and charged with murder in the first degree. He also became suspected of poisoning his father, but that claim was not investigated further. Latimer’s trial was sensationalized by the media due to his good looks and undeniable wit and charm. He became known as “The Infamous Matricide.” Until the facts of the case were laid out, he even had the support of many high society members in Jackson as he clung to his innocence. But the jury was not fooled, and after deliberating for just 17 minutes, they came back with a guilty verdict. Latimer was sentenced to life in prison at the Michigan Penitentiary in Jackson at the age of 23.

Now. Are you ready for things to get really demented?

Irving Latimer quickly made a name for himself at the Michigan Penitentiary. He was well-known and well-liked by both prisoners and prison staff. He became good friends with the Commander of the night shift, Captain Maurice Gill, as well as other officers and guards. By 1893, Latimer had the run of the prison. He was allowed out of his cell at night to cook and do work for the staff. Many nights, however, he could be found sitting in Captain Gill’s office chatting away as if they were old friends. This is how he gained their trust. The people paid to guard him let their guards down. And so they never saw him coming.

On March 27, 1893, Irving Latimer prepared a late night meal for the prison staff with two special ingredients- prussic acid (also known as cyanide) and opium. While opium was contraband not hard to come by in prison, the prussic acid was actually ordered through the prison pharmacy at Latimer’s request. The Clerk of the Penitentiary, another unwitting pawn of Latimer’s, actually picked the poison up from the pharmacy and delivered it to Latimer’s cell! Latimer would later claim that he’d researched the effects of opium and prussic acid extensively, and only intended to render the prison staff unconscious so that he could escape. It worked. Several officers collapsed soon after eating the tainted meal, including Captain Gill and Officer George Haight, who held the keys to the prison. Once the men were unconscious, Latimer put his plan into action. As he was robbing Officer Height of gold coins and the prison keys, a guard who hadn’t been poisoned heard the commotion and approached. Latimer told him Officer Haight was dying, and that he would go get help. Instead, he took the keys and cash, armed himself with two guns from the gun locker, unlocked the prison’s front gate, and walked out. Captain Gill and most of the others regained consciousness within a few hours and alerted authorities to Latimer’s escape, but Officer Haight was not so lucky. He died on the prison floor shortly after his body was ransacked for keys and money.

Two days later, Irving Latimer was captured in Jerome, Michigan, a small town south of Jackson, when he tried to buy shoes with one of the $5 gold pieces he’d stolen from Officer Haight. He was transported back to the Michigan Penitentiary, where he was locked inside a bare cell which was then boarded up from the outside. The majority of the officials working at the prison were fired. Some of them, including Captain Gill, faced criminal charges.

Latimer was never charged with the murder of George Haight. It was deemed unnecessary since he was already serving life for the murder of his mother. In an attempt to minimize the appearance of damage caused by the prison’s negligence, Haight’s murder was largely ignored. Seven years after his death, his widow was finally awarded compensation in the amount of $25 monthly, not to exceed $3000 total, by the prison. George Haight, the first-ever Michigan Department of Corrections employee to be killed in the line of duty, was not properly honored until 122 years after his death, when his name was added to the Michigan Fallen Heroes Memorial in Pontiac.

Irving Latimer remained at the Michigan Penitentiary for decades. When the new prison was built, a small group of elderly lifers remained at the old prison for upkeep and maintenance purposes, including Latimer. He was the very last prisoner to leave the Michigan Penitentiary, in fact. He was pardoned by Governor William Comstock in 1935 at the age of 70 after serving 45 years for the murder of his mother, and zero years for the murders of his father and George Haight. He took a job working for Ford Motor Company, but fell ill soon after and was sent to the Eloise Asylum, where he died in 1945. He was 80 years old.

THE HOLT SLAYERS

On the morning of April 24, 1972, a Holt, Michigan resident heard a quiet knock at her front door. Little did she know that what awaited her on the other side would rock her small community to its core. On her porch stood the four-year-old boy who lived next door. “Momma won’t wake up, and Debbie has blood coming out of her nose,” he cried. He explained how he had hidden on the stairs while two men broke into his home and attacked his family. The men were gone now, and his family needed help.

On the morning of April 24, 1972, a Holt, Michigan resident heard a quiet knock at her front door. Little did she know that what awaited her on the other side would rock her small community to its core. On her porch stood the four-year-old boy who lived next door. “Momma won’t wake up, and Debbie has blood coming out of her nose,” he cried. He explained how he had hidden on the stairs while two men broke into his home and attacked his family. The men were gone now, and his family needed help.

The neighbor entered the boy’s home and found his mother, 38-year-old Ruth Parrish, dead on her bedroom floor, her body riddled with bullets. Upstairs, she found the boy’s very pregnant step-sister, 17-year-old Debbie Berger, shot to death in her bed. Both women were still in their pajamas. The 911 call was placed just after 9am, and the manhunt for those responsible for the triple murder began.

The search didn’t last long. Two 18-year-olds, Wayne Gilbert Jr. and Steven Lange, were arrested in Wisconsin the following day. While the teenagers were not locals, they weren’t strangers either. At least not to the Parrish family. Wayne Gilbert was the ex-boyfriend of Debbie Berger, and the father of her unborn child. Debbie and her mother had just filed a paternity case against Wayne in Wisconsin shortly before the murders. Prosecutors pointed to this as their motive.

Officials claimed that the two intended to kidnap Debbie and her mother, take them to Chicago, and force Debbie’s mother to consent to an abortion. (Debbie was underage, and therefore could not consent herself.) The men traveled to Michigan the Friday before the murders, stayed in a Lansing hotel over the weekend, then woke up early Monday morning and slammed back over a dozen beers before heading to the Parrish home around 8am. They waited for Mr. Parrish to leave for work before going inside. It is believed that Steven Lange went upstairs to get Debbie, who was seven months pregnant, while Wayne Gilbert went and found Mrs. Parrish in her bedroom. Suddenly gunshots rang out from the first floor of the home, and Wayne yelled up the stairs, “I’ve just done the job on the old lady, you’ll have to kill Debbie!” Knowing that their plan had gone horribly wrong, but that he couldn’t leave a witness behind, Steven Lange shot Debbie Berger six times. One of those bullets severed her umbilical cord, killing her unborn child. The men ran from the house, but once they were outside, Wayne went back in. He had to see that Debbie was dead for himself. Once inside, Wayne fired one more shot into Debbie’s body just to be sure.

Both men confessed their crimes to police in Wisconsin before being extradited back to Michigan. But once in the Ingham County Jail, they quickly turned on one another.

Wayne Gilbert’s trial was first. He argued that he loved Debbie and planned to marry her and support their child, and that he and his friend were just visiting for the weekend. He said he was waiting outside while Steve went into the house to talk to the women, and that there was never any plan to hurt them. He was shocked when the shooting began. According to him, Steven murdered both women for no apparent reason. He went on to explain that his prints were only all over the crime scene because after the shooting, he went inside and held Debbie in his arms as she died, professing his undying love. The judge didn’t buy it, and convicted Wayne of first degree murder.

During Steven Lange’s trial, he corroborated the prosecution’s case- that he only shot Debbie because Wayne had murdered Mrs. Parrish, and he was afraid to leave a witness. He was convicted of first degree murder as well.

But Wayne Gilbert refused to allow the Parrish family to have peace. He filed appeal after appeal, and had two guilty verdicts overturned. It wasn’t until his third trial, in which he represented himself, that his own mother was brought in as a surprise witness for the prosecution. When she testified that her son confessed to her the day he was arrested, the matter was put to rest once and for all. Wayne Gilbert is serving out multiple life sentences in an Ionia prison. Steven Lange was paroled in 2017. (Pictured: The Parrish Family Home.)

MOMMY DEAREST

In May 1893, Okemos wife and mother Minnie Herre was arrested for the murder of her 12-year-old son following a bizarre series of events. It all began when Mrs. Herre fed her son a piece of pie laced with the poison “Rough on Rats.” The boy fell ill, and died within a couple of days. Foul play was not initially suspected. A coroner’s inquest was planned to determined the cause of death. The night before the inquest, which was to be followed by the boy’s funeral, an unsettling scene unfolded at the Herre estate. Family members sitting up with the boy’s body were startled by the smashing of a window. The gust of wind that rushed through the house caused the lights to go out. When the lanterns were re-lit, it was found that the boy’s body had been stolen from the home. The following morning, the corpse of Minnie Herre’s son was found at the bottom of a deep well, and all of the animals on the farm had been killed. Police were called, and Mrs. Herre admitted to poisoning her son, then stealing the body in an attempt to conceal her crime. She began screaming and tearing at her hair as she was taken into custody. In jail, her mental state continued to deteriorate. She was declared insane, and was sent to the Asylum for the Dangerous and Criminally Insane in Ionia. A year and a half later, Minnie Herre was determined to be fit for trial, and was moved from Ionia to Lansing to finally stand trial for her son’s murder. She was found not guilty by reason of insanity. It was ordered that: “Steps will be taken to have the woman confined in an insane asylum, as she is believed to be a person in whose hands the lives of her remaining children are not safe.” But just two weeks later, doctors declared her “wholly cured” from her bout of insanity, and she was released. She stopped making headlines after that, so it’s hard to say whatever happened to Minnie Herre, but I would imagine she didn’t find a career as a baker.

In May 1893, Okemos wife and mother Minnie Herre was arrested for the murder of her 12-year-old son following a bizarre series of events. It all began when Mrs. Herre fed her son a piece of pie laced with the poison “Rough on Rats.” The boy fell ill, and died within a couple of days. Foul play was not initially suspected. A coroner’s inquest was planned to determined the cause of death. The night before the inquest, which was to be followed by the boy’s funeral, an unsettling scene unfolded at the Herre estate. Family members sitting up with the boy’s body were startled by the smashing of a window. The gust of wind that rushed through the house caused the lights to go out. When the lanterns were re-lit, it was found that the boy’s body had been stolen from the home. The following morning, the corpse of Minnie Herre’s son was found at the bottom of a deep well, and all of the animals on the farm had been killed. Police were called, and Mrs. Herre admitted to poisoning her son, then stealing the body in an attempt to conceal her crime. She began screaming and tearing at her hair as she was taken into custody. In jail, her mental state continued to deteriorate. She was declared insane, and was sent to the Asylum for the Dangerous and Criminally Insane in Ionia. A year and a half later, Minnie Herre was determined to be fit for trial, and was moved from Ionia to Lansing to finally stand trial for her son’s murder. She was found not guilty by reason of insanity. It was ordered that: “Steps will be taken to have the woman confined in an insane asylum, as she is believed to be a person in whose hands the lives of her remaining children are not safe.” But just two weeks later, doctors declared her “wholly cured” from her bout of insanity, and she was released. She stopped making headlines after that, so it’s hard to say whatever happened to Minnie Herre, but I would imagine she didn’t find a career as a baker.

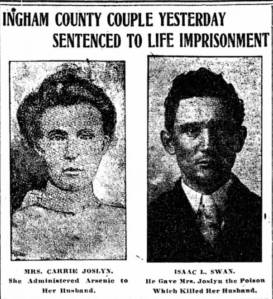

THE BLACK WIDOW OF DANSVILLE

“My heart was starving for kindness and that is the whole story. My husband was distant and aloof. A wife wants to be kissed, petted, made much of- she does not forget after marriage all that she liked before.” This was housewife Carrie Joslyn’s justification for her affair with her husband’s farmhand, which ultimately led to murder.

“My heart was starving for kindness and that is the whole story. My husband was distant and aloof. A wife wants to be kissed, petted, made much of- she does not forget after marriage all that she liked before.” This was housewife Carrie Joslyn’s justification for her affair with her husband’s farmhand, which ultimately led to murder.

William Joslyn was a wealthy farmer in Dansville, Michigan in the late 1800s. His wife, Carrie, was many years his junior, and was said to be smart as a whip and exceptionally beautiful. Together, they had two children. As William was often away on business, he decided that Carrie should have some help around the house. Carrie wished to bring in a nanny or maid, but William insisted that his farmhand, a young widower by the name of Isaac Swan, could do the work. It would prove to be a fatal mistake.

Isaac Swan had two children of his own that were just a couple of years older than the Joslyn children. He was said to be a kindhearted man who cooked “as good as any woman.” Together in the Joslyn household day after day, the lonely widower and the neglected housewife began to spark rumors around town. Carrie Joslyn always maintained that the relationship was not romantic in any way. But Isaac Swan told his closest confidants of a torrid love affair, one so scandalous that when it was retold at his trial, all of the women in the courtroom had to be escorted out “for decency’s sake.”

On Christmas Day 1904, William Joslyn died in his bed after weeks of illness. His cause of death was listed as “malignant measles,” even though the doctor who had been tending to him suspected from his first visit that Joslyn was being poisoned. Even though Joslyn told friends and family that visited him that he thought he was being poisoned. Even though he’d confided in his lawyer months earlier that he thought Carrie was trying to kill him.

When William’s lawyer heard of his passing, he traveled to Dansville and told police of his client’s belief that his wife was having an affair with the farmhand, and that she was trying to kill him. Officials exhumed William’s body and had a proper autopsy performed, at which point it was determined he had actually died from arsenic poisoning, not measles.

According to prosecutors, Carrie Joslyn and Isaac Swan were in love, and they conspired to kill William so that they could marry and raise their children together. In early December 1904, Isaac purchased a bottle of arsenic from Lezler’s Drug Store in Williamston and gave it to Carrie. On December 10th, Carrie slipped the first dose of arsenic into her husband’s coffee. He immediately fell ill. Over the next two weeks, she served him arsenic-laced coffee, tea, and lemonade on his sick bed. No one made any attempt to stop her, despite the doctor’s suspicions and William’s accusations that he was being poisoned. He ultimately expired on Christmas Day.

Carrie was arrested shortly after the start of the new year in 1905. She first attempted to claim insanity, but quickly changed her mind and pled guilty to murder. Isaac Swan was arrested in New York after a brief manhunt, and pled not guilty at his arraignment.

According to Carrie, she was unhappy in her marriage, but was not unfaithful, and had never thought about killing her husband until the day Isaac Swan handed her a bottle of arsenic. She claimed that her husband and his farmhand got into a disagreement, and the next day an angry Isaac handed her a package that he said contained poison, and suggested she use it to dispose of her husband.

Isaac’s story was, of course, quite different. He claimed that he and Carrie were in love, and that he would have done anything for her, so when she asked him to obtain a bottle of arsenic for her, he obliged. He was aware of her intentions, but had no role in the murder other than to pick up a legal substance at the drugstore for his employer’s wife at her request.

The judge believed neither of them, and sentenced them both to life in prison. The Joslyn children were three and five, while the Swan children were six and eight at the time. All four became orphans that day. After serving eleven years of his sentence, Isaac Swan was paroled in 1916. He remarried and lived a long, happy life. He died in 1953 at the age of 79. Carrie Joslyn’s sentence was commuted in 1925, after she’d served 20 years. She also remarried, and passed away in 1932 at the age of 59.

WHITE WEDDING

January 12, 1935 was to be a glorious day at the Enslen Farm in Angola, Indiana. The farmer’s daughter, Billie Jo, was set to marry her sweetheart Charles Good, a factory worker from Bronson, Michigan. As the big day approached, Mr. Enslen ordered all of his workers to ready the estate for his daughter’s wedding, including his farmhand William Mahler. But as the Enslen family was preparing for a wedding ceremony, William Mahler was preparing for something else. Unbeknownst to his boss, William was also in love with Billie Jo. He considered Charles Good his rival, and he did not intend to watch his beloved marry another. Two days before the nuptials were to take place, he put his deadly plan into motion.

On January 10th, just as the crew at Bronson Reel Company was returning from lunch, William Mahler arrived and asked the foreman for permission to excuse Charles Good for the day. He told Charles that Billie Jo had fallen ill and needed him to go to her. The two men got into Charles’ car and headed for the farm in Angola.

A short time later, just five miles outside of Bronson, 19-year-old John Unterkircher noticed a car stopped alongside the road. Two men got out of the vehicle and began fighting. And then, as the teenager watched in horror, one of the men pulled out a hatchet and struck the other man nearly a dozen times. Once the man who’d been attacked appeared to be dead, the hatchet-wielding maniac got back into the car and drove off. John Unterkircher rushed the mortally wounded stranger to the local emergency quarters, which conveniently doubled as the undertaking parlor. But with eleven hatchet wounds to the head, the man didn’t stand a chance. Charles Good was pronounced dead at 3:45pm, less than 48 hours before his wedding.

Almost as quickly as Charles Good was identified, the police were on the trail of his killer. The foreman at Bronson Reel Company told authorities that Good had left with his fiancee’s farmhand, so police headed to the Enslen farm in Angola to find William Mahler. By the time they arrived, William Mahler was cool, calm, and collected. He’d had just enough time to dispose of his bloody clothes. Or so he thought. He proclaimed his innocence at first, but when he was brought before the judge, he was asked why his hat (which he’d forgotten to remove in his haste) was stained with fresh blood. He quickly broke down and confessed.